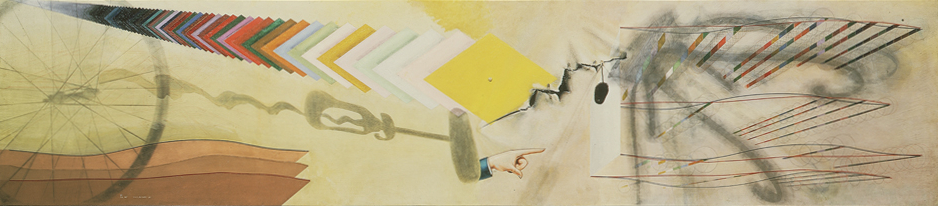

Tu m' — 1918

Surface Rupture • Artistic Citation

Surface Rupture — Final Exit from Painting

Tu m’ is Marcel Duchamp’s last oil painting—and perhaps his most defiant. Created in 1918 for the library of Katherine Dreier, a patron and future co-founder of the Société Anonyme, the work is both a farewell and a final demonstration: a painting that physically turns against itself.

What begins as a traditional rectangular canvas erupts into something far stranger. A real bottle brush is mounted directly into the surface, rupturing the illusion of the painted plane. Torn muslin at the far end evokes a literal wound.

The perspective is skewed, the shadows artificial, and a row of pierced holes leads the eye toward escape.

This isn’t a painting about representation—it’s a painting about the end of painting.

Surface Rupture as Coded Gesture

Tu m’ is the most extreme early use of the gesture now known as Surface Rupture—a deliberate breakdown of pictorial coherence through physical intrusion. The painted surface doesn’t just fracture conceptually, it is violated materially.

With its inclusion of a real brush (formerly a tool of painting) now rendered useless, Tu m’ dissolves not only the image but the medium itself.

From Morée to Tu m’

If Morée (1916/17) quietly introduced Surface Rupture—through abrasions, ink removal, and the partial destruction of a signature—Tu m’ shouts it. In hindsight, Morée reads like a prototype. Tu m’ is the final instruction. Duchamp didn’t just abandon painting—he taught it to dismantle itself first.

This was not resignation. It was sabotage with precision. And it was the last painting he ever made.