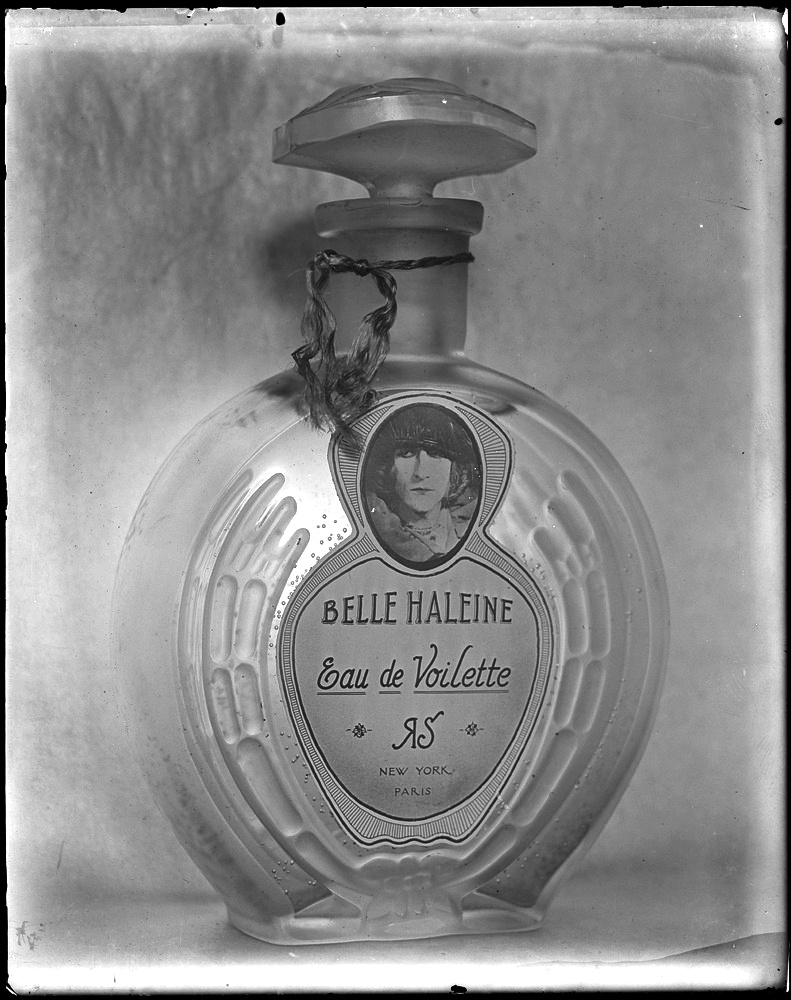

Belle Haleine — 1921

1. Another String of Pearls

The pearls in Morée are visually central—deliberately placed, yet strangely detached from their

traditional meaning.Against the backdrop of a rising black wave, the pearls appear fragile and out of place—caught

in motion, as if about to be overtaken. Their placement suggests not luxury, but vulnerability.

Pearls appear again in Belle Haleine, now worn by Duchamp in drag. Their presence is one of several

links between the two works. In both, the pearls help shift the tone from glamour to irony.

They aren’t there to decorate—they’re there to disrupt. As part of a larger visual and conceptual connection

to Morée, the pearls help signal a shared intent: to turn the language of commercial art against itself.

2. A Planted Backdrop

At first glance, it’s easy to mistake the backdrop in Belle Haleine for a simple studio flourish—

a bit of theatrical drapery to set off the bottle and draw focus to the face of Rrose Sélavy.But the backdrop is far from arbitrary. It isn’t just decorative—it’s photograph of a painting.

Closer inspection reveals that the image behind the bottle was created using the same

subtle wash-and-remove technique seen in Morée.

This is the Veil Water process: a subtractive method in which ink or dye is rinsed away and repelled

to form atmospheric effects, soft gradients, and hidden contours. What looks like photographic blur

or design texture is, in fact, a hand-crafted surface that points directly back to Morée.

That connection changes how we understand Belle Haleine. The backdrop isn’t just framing the image—

it’s part of its meaning. It reveals a deeper level of collaboration between Duchamp and Man Ray,

one grounded not just in persona, but in process.

3. “Veil Water” The Perfume

The name “Veil Water” comes directly from Belle Haleine, Duchamp’s 1921 perfume-bottle readymade.

We’ve adopted the term to describe the subtractive wash technique seen in Morée—a process where

ink or dye is applied, then rinsed or lifted to create cloud-like gradients and drip patterns.

This isn’t just a convenient label. We believe Belle Haleine was titled Eau de Voilette—Veil Water—

in deliberate reference to the same process used in Morée.

The name itself may be a coded acknowledgment of the shared technique present in both works.

4. Subverting the Commercial Image

Morée and Belle Haleine share a common strategy: they both mimic the language of

commercial art in order to undermine it.At first glance, Morée looks like an Art Deco fashion illustration, complete with graceful

lines and a string of pearls. But its dissolving forms, subtractive technique, and haunting

wave all push against the surface appeal—turning elegance into critique.

Belle Haleine follows a similar path. Framed as a perfume advertisement, it borrows

the polished style of product photography, only to insert Duchamp in drag at the center.

The joke is layered, but pointed: the bottle is fake, the brand is made-up, and

the glamour is an illusion.

In both works, commercial aesthetics are used as bait—but what they deliver is something

entirely different. Together, they expose and dismantle the machinery of surface-level appeal.

5. A Possible Nod to Nude No. 3

Belle Haleine is most often described simply as a photograph of a perfume bottle, but in fact, it is

a photograph of a photograph of a perfume bottle—an easy-to-miss doubling that subtly distances

the viewer from the object.This emphasis on photographic layering may serve as a quiet nod to the process behind Duchamp’s Nude No. 3, which was itself guided by a photograph and marks the first appearance of the Veil Water effect.

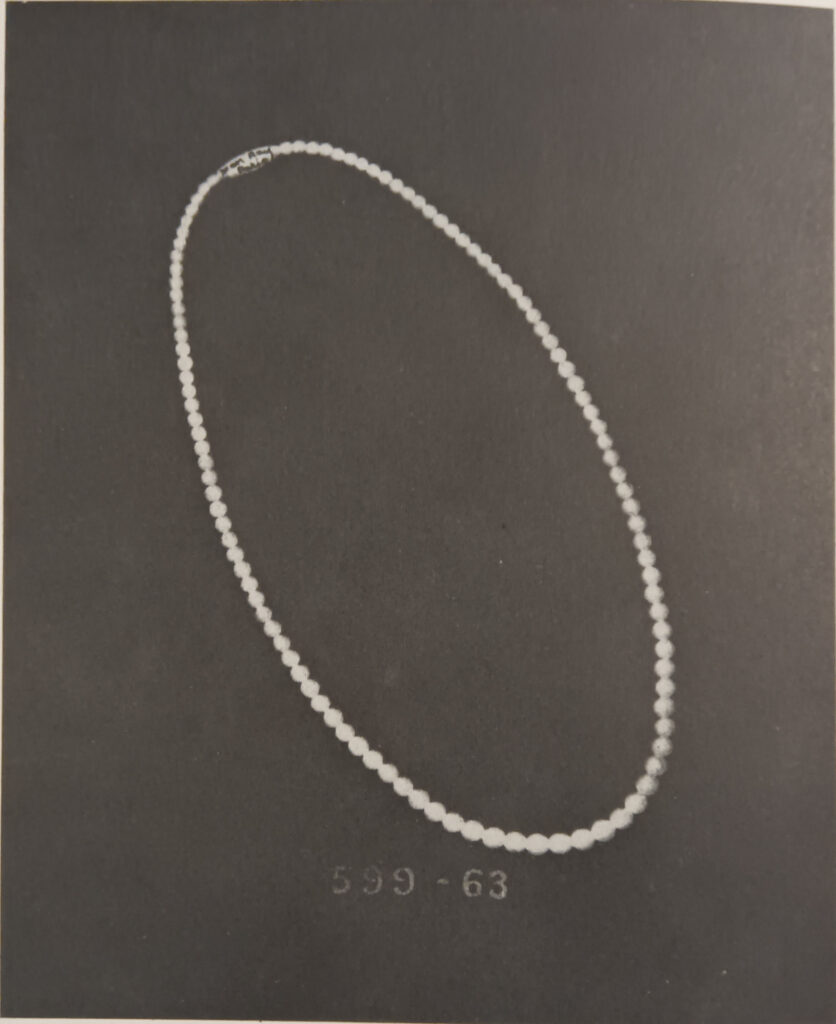

6. String of Pearls in 391 (1924)

In 1924, on page 4 of Picabia’s 391, Issue No. 18, a striking full-page image

appears: a single string of pearls, elegantly draped across a dark field.

On the clasp, in small text, is inscribed: “Man Ray, Paris.”This is not fashion. This is code.

The image functions as both mock advertisement and conceptual signature.

Pearls—long associated with bourgeois femininity, fashion excess, and

surface display—were already a recurring motif within Dada. Here, they are

isolated, commercialized, and rebranded under Man Ray’s name, turning

luxury into language.

This confirms that the pearl motif was active, shared, and deliberate within the Dada visual lexicon. And given the timing and placement, it may also serve as a conceptual echo

of Morée—the painting where the pearls first appear not as decoration, but as critique.