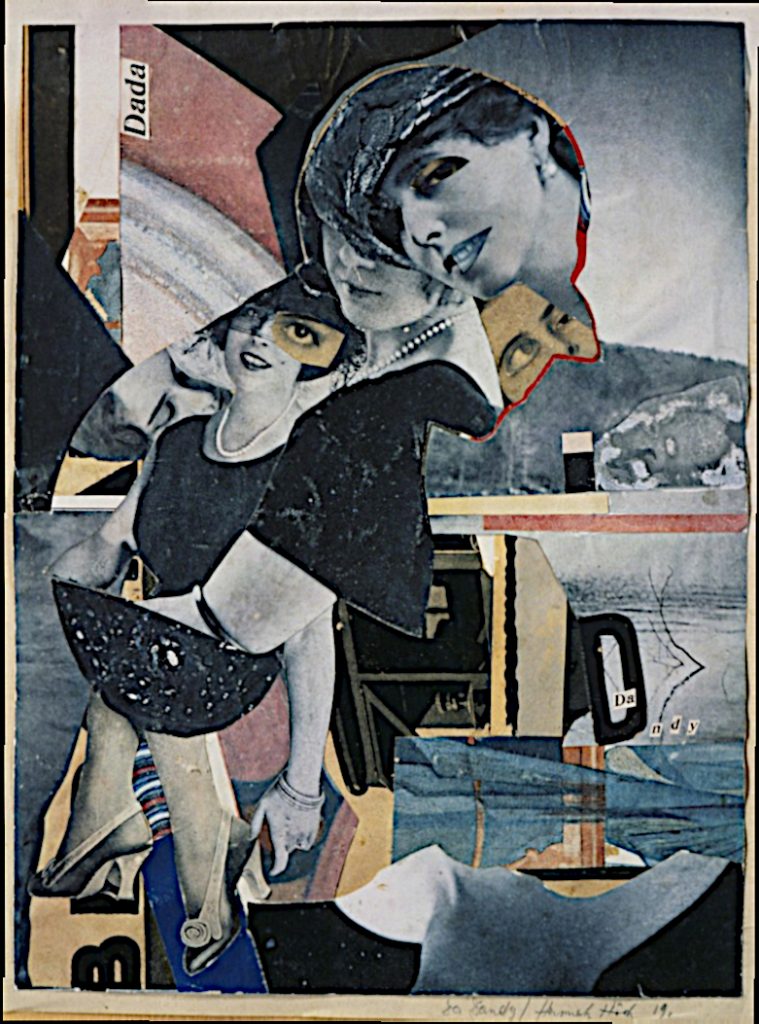

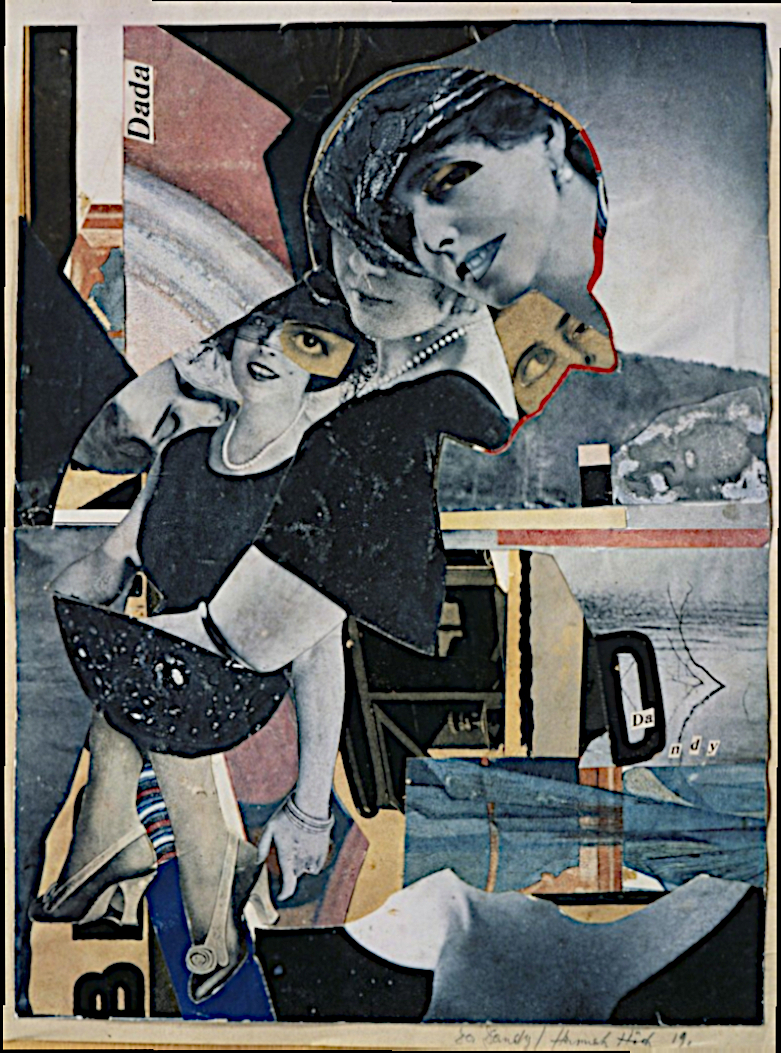

Hannah Höch's

Da-Dandy — 1919

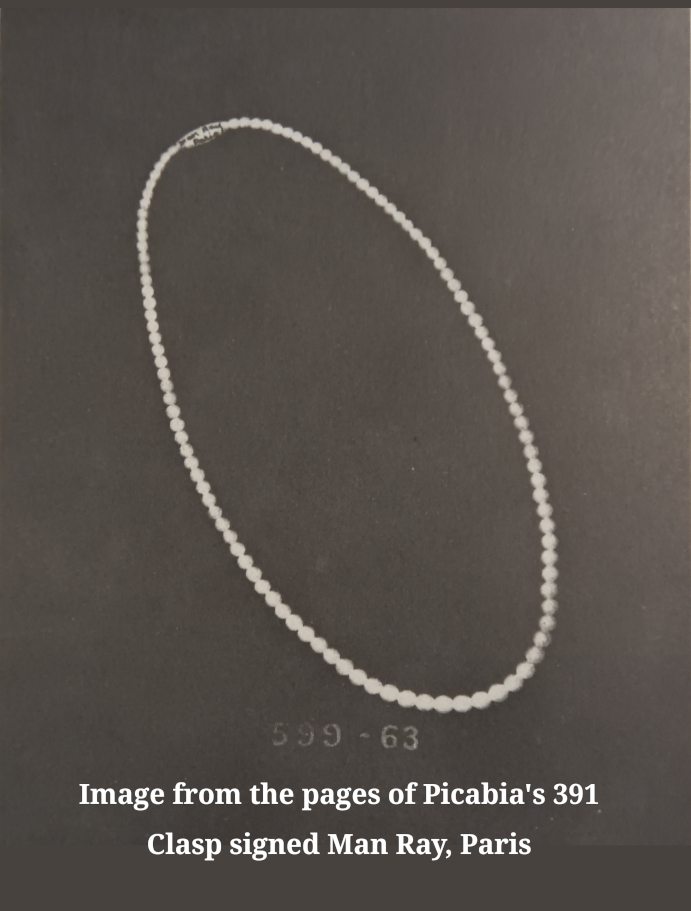

Bourgeois Pearls

With the exception of Picabia’s “Jeanne Marie Bourgeois”, the early works that echo Morée share three defining elements: a ‘string of pearls’, a subtle reference to the ‘Veil Water’ effect, and a likeness of Duchamp—each time, whether in shadow or in drag, cloaked in vagueness.

Morée is the first to turn pearls against themselves—not to adorn, but to undermine—to expose bourgeois excess through its own icon.

In the works that follow, they appear more subtly, refracted through different hands and media, but unmistakably present.

In each case, the pearls stand in for bourgeois luxury—fragile, decorative,

and ripe for critique.

A Slow Burning Fuse

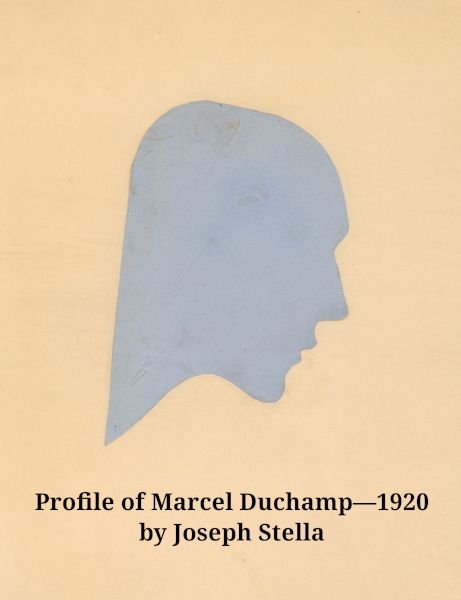

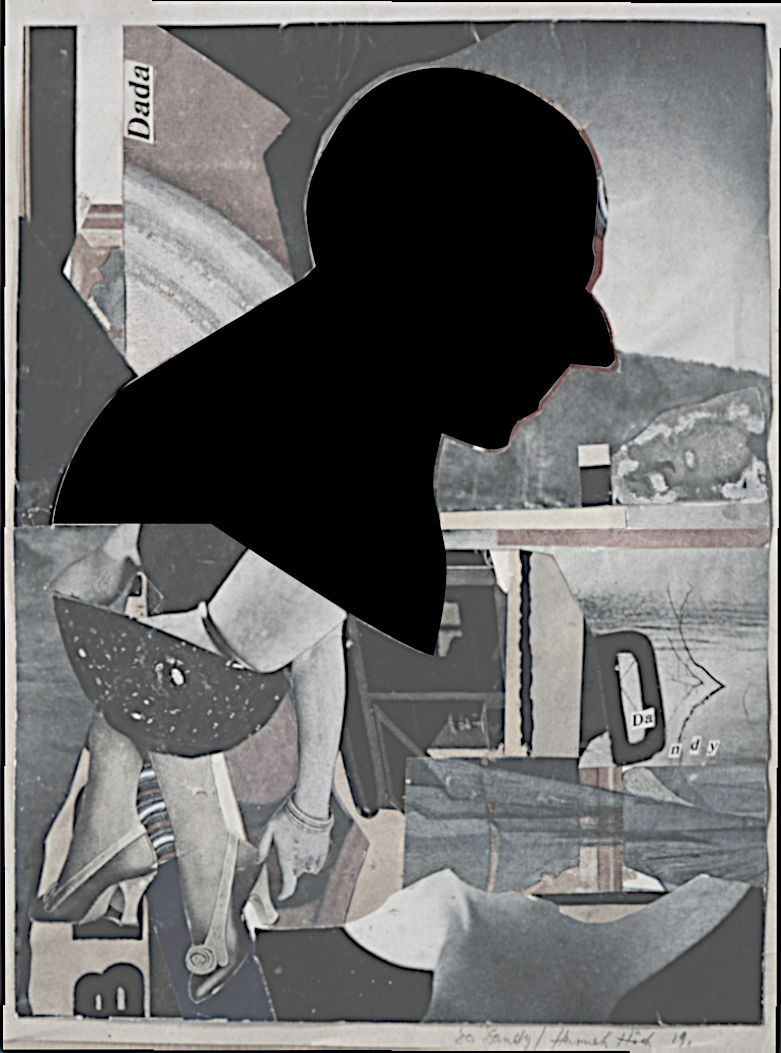

You may—or may not—have seen it right away, but in Da-Dandy, there is a silhouette of a male figure outlined in profile.

Until now, the central figure in Höch’s Da-Dandy has been treated symbolically—a critique of masculinity, a fragmented dandy, a cultural type. Scholars have explored what he represents, but rarely asked who he might actually be.

But now, through the lens of Morée, a clearer image begins to emerge. The downward gaze, the distinctive head tilt, the pearls, the placement of a Veil Water background—all point to something more specific. This may not be a generalized figure at all, but a portrait—quiet, unclaimed—of Marcel Duchamp himself.

In 1957, Hannah Höch’s work was experiencing a resurgence of attention in Germany. That year, Höch presented 26 new collages at Galerie Gerd Rosen in Berlin, marking a significant exhibition of her work.

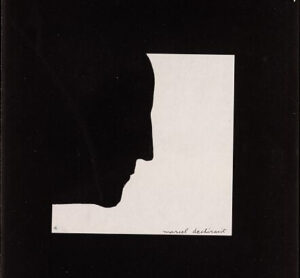

That same year, Duchamp created a self-silhouette.

Was Duchamp telling us—years later—that he was the figure in

Da-Dandy, or maybe even Da-Dandy himself?

A Veil Water Implant

Hannah Höch seems to have known at least part of the story.

In Da-Dandy, she doesn’t just use the halftone background, she builds her entire composition around what now appears to be a profiled figure of Duchamp, carefully silhouetted against that veiled field. And surrounding him? Pearls—one of Dada’s visual codes for bourgeois femininity, already active in Duchamp’s and Man Ray’s work.

Taken together, these elements suggest Höch wasn’t working randomly.

She was working within a shared visual language—referencing

figures in her circle, using their cues, and repurposing their imagery

with precise, pointed intent.