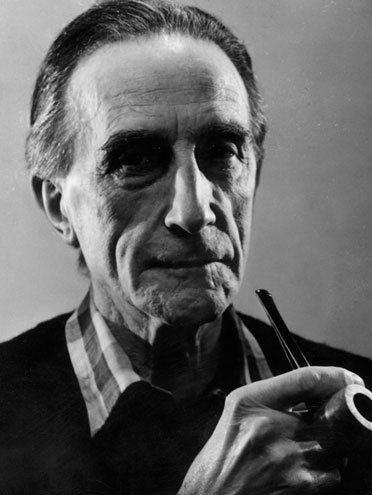

The Master Provocateur of New York Dada

Marcel Duchamp was not just a participant in New York Dada—he was its strategist, theorist, and invisible architect. His fingerprints—sometimes literal, more often conceptual—appear in nearly every major instance where Dada begins to encode what we now call Dada's Five Coded Gestures:

- Refusal of Authorship

- Parody of Glamour

- Drips as Sabotage

- Function Denied

- Surface Rupture

These gestures, often buried in playful or cryptic visual forms, are rarely isolated from Duchamp’s influence. Even when he was not the named creator, his thinking shaped the result.

Present Even in Absence

From Fountain (1917) to Belle Haleine (1921), Duchamp demonstrated or inspired nearly every conceptual tactic that defined the Dada shift from object-making to idea-making. He left painting behind—but not image-making. Even his apparent silence was a maneuver, a gesture of authorship by refusal. Works like Picabia’s Mistinguett or Man Ray’s Gift seem independent at first glance, but upon inspection, they echo Duchamp’s earlier strategies—or answer them. It is no accident that the most potent examples of these gestures almost all radiate outward from his ideas. And when an anomaly appears—such as Morée—it feels less like an outsider’s rebellion and more like a prototype he quietly planted.

The Strategist Behind the Curtain

Why did others orbit Duchamp so faithfully? Much of it comes down to

power and access. Duchamp had two enormous advantages that most avant-garde artists of the time did not:

- The Arensbergs – His close friendship with Walter and Louise Arensberg placed him at the heart of New York’s most powerful Dada-adjacent salon. They collected him, defended him, and funded the space in which Fountain could exist.

- Katherine Dreier – As co-founder of the Société Anonyme with Duchamp, Dreier positioned him as a co-curator of modernism. She trusted him not just with artworks, but with intellectual authority.

These alliances elevated Duchamp into a role

neither Picabia nor Man Ray could match. He was not the most prolific, but he didn’t need to be. He supplied the code. The others followed it—sometimes riffing on it, sometimes literalizing it.

The Quiet Control

Duchamp’s brilliance wasn’t just in the works he made—it was in the system he built. He created a structure in which

ideas, not images, were the true currency, and then let others fill in the blanks. Picabia broadcast the signals. Man Ray collaborated across media. But Duchamp was the Watcher. The Ghost Engineer. The Master Provocateur.

Whether or not he painted Morée, its logic belongs to him. It speaks his language—before anyone else dared to.